Uganda's Treacherous Path: A Shs34tn Gamble on Debt and Unproven Revenue

A stark warning has been issued from the corridors of parliamentary oversight, painting a grim picture of Uganda's fiscal health.

The Shadow Minister for Finance, Ibrahim Ssemujju Nganda, has cast a critical spotlight on the government's ambitious, and arguably perilous, plan to fund its next budget, posing a fundamental question that cuts to the heart of the nation's economic sovereignty: "Who will lend us Shs34 trillion?"

The query is not rhetorical. It is a direct challenge to a government increasingly cornered by its own debt and what critics are calling a dangerously optimistic revenue strategy.

According to an analysis of the Ministry of Finance's own Medium Term Debt Management Strategy, the well of cheap, long-term loans is running dry.

Global creditors, focused on their own post-recession economic recovery, are tightening their purse strings.

The consequence for Uganda is a dramatic and high-stakes pivot towards domestic borrowing. A staggering 68% of the required loans will be sourced from local commercial banks.

This shift effectively forces the government to compete with its own private sector for credit, a phenomenon known as "crowding out," which stifles business growth and investment.

The terms of this new debt are unforgiving. A mere 9% of the loans to be procured will be concessional (with low interest and long repayment periods).

The vast majority will be on semi-concessional (6%) and, more alarmingly, non-concessional and commercial terms (16.7%).

This is a stark departure from the government's own stated policy to restrict these expensive commercial loans to infrastructure projects capable of generating revenue for their own repayment.

Ssemujju points to a critical breach of this fiscal discipline, noting the government is now "contracting non-concessional loans to fund recurrent expenditures."

This is akin to taking out a high-interest mortgage to pay for groceries – a financially unsustainable path. The cost of this strategy is already crippling the budget.

This financial year alone, Uganda is slated to pay a colossal Shs 9.4 trillion in interest, primarily to domestic commercial banks, with an additional Shs 1.8 trillion in interest to foreign lenders.

The upcoming budget sees no reprieve, with interest payments projected to consume over Shs9 trillion once again.

The Ministry of Finance itself, in a moment of candid self-assessment within its strategy documents, acknowledges the precariousness of the situation. It complains of "expenditure requirements against realistic revenue projections which is raising the fiscal deficit and leading to more borrowing."

It further concedes that rising interest rates and a depreciating shilling have "increased the borrowing costs and worsened Uganda's debt burden amidst reduced foreign exchange reserves."

A Revenue Target Rooted in Hope, Not History

The government's primary answer to this debt conundrum is to task the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) with an unprecedented collection target of Shs 34 trillion for the next financial year—a significant leap from the current year's Shs 29.3 trillion target.

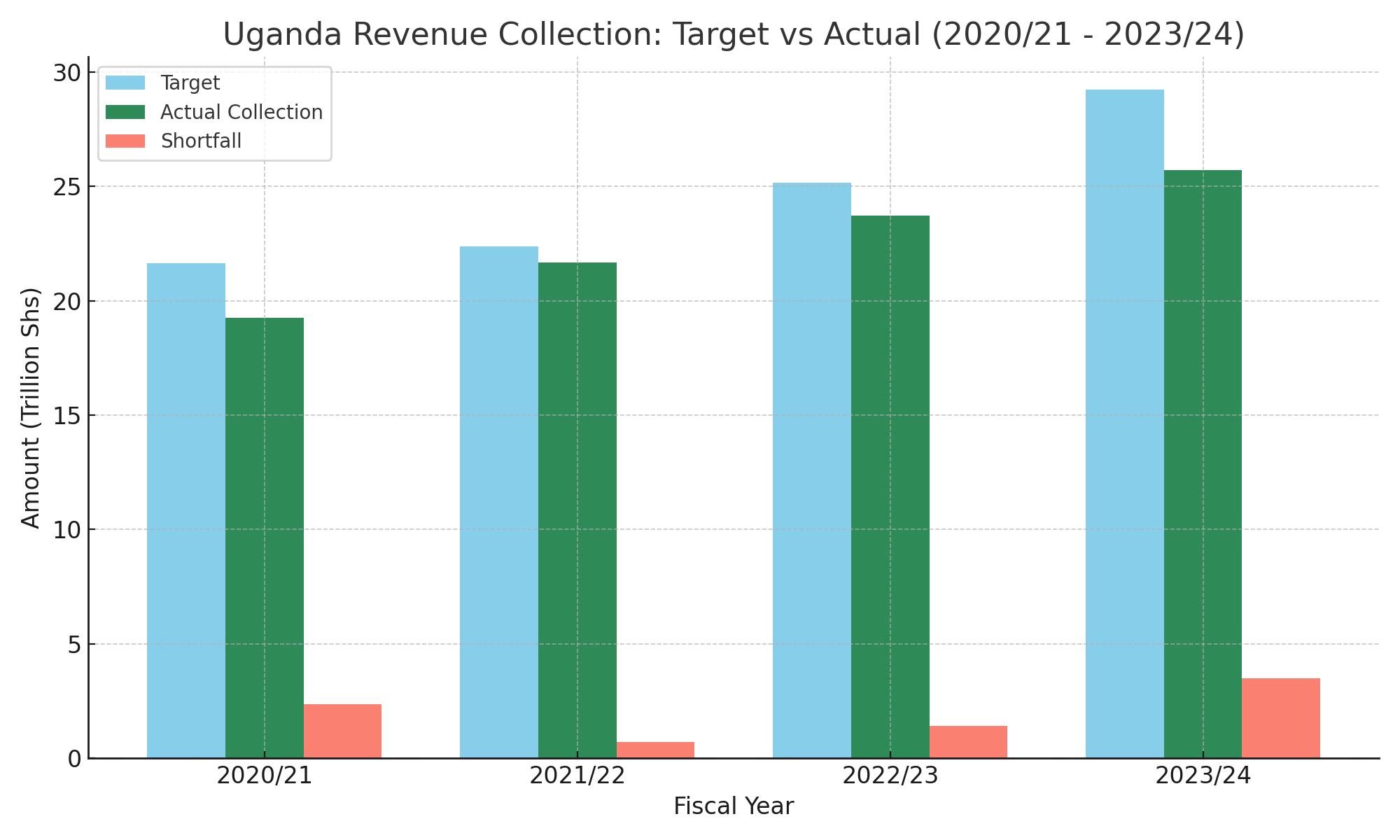

However, a critical look at the URA's recent performance reveals a troubling pattern that undermines this optimism. For the last five consecutive years, the tax body has failed to meet its collection targets.

The data shows a consistent and significant gap between ambition and reality.

To expect the URA to not only close this historical gap but to also collect an additional nearly Shs5 trillion is, in the view of the shadow minister, a fiscal fantasy.

The new Shs34 trillion target is broken down into ambitious figures across the board, from a Shs12.9 trillion target in direct domestic taxes, including a hefty Shs6.3 trillion from Pay As You Earn (PAYE), to a Shs12.6 trillion goal from international trade taxes, heavily reliant on petroleum duties.

This creates a vicious cycle. When the almost inevitable revenue shortfall occurs, the government will be forced back to the loan market to plug the deficit.

This will mean seeking more of the very same high-interest, non-concessional loans that are already inflating the national debt and consuming a vast portion of the budget in interest payments.

The critical story emerging from shadow minister Ssemujju's analysis is one of a government caught between dwindling access to affordable credit and a reliance on unrealistic revenue projections.

It is a narrative of escalating risk, where the very mechanisms designed to fund the nation's progress are now threatening to become the primary drivers of a full-blown debt crisis, leaving the economic future of Uganda hanging precariously in the balance.

0 Comments