Uganda should reshape its growth path

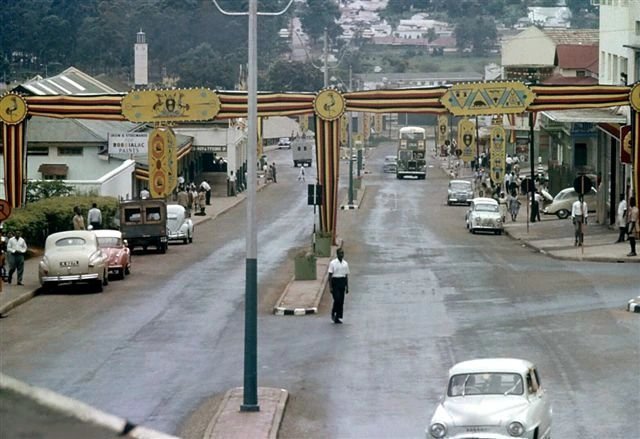

Kampala streets in 1960s

Uganda’s development story is shaped by two powerful histories.

The first is our real, lived past. Before colonialism, Uganda had functioning kingdoms, trade networks and organised communities. This was violently disrupted by European colonization – a clear example of what Karl Marx described as “primitive accumulation.”

Land was taken, people were forced into labour, and resources were extracted and shipped abroad. Uganda did not grow poorer by accident; it was made poorer so Europe could grow richer.

Cities such as Manchester and Birmingham were built partly with wealth taken from places like ours. Ugandans who resisted this theft, including leaders such as Muhumuza in Kigezi, paid with their lives. The second history began after independence. We were told that development followed a simple, universal path, famously described by economist Walt Rostow.

Build roads, educate people, support business, and wait for economic “take-off.” This story asked us to forget how badly our starting point had been damaged. It assumed every country began the race from the same line.

Decades later, that promised take-off still feels distant. Uganda continues to export raw coffee, minerals and cheap labour, while richer countries sell finished goods and control the rules of trade. Uganda is, therefore, trapped between two stories.

If we accept Rostow’s development blueprint without question, we ignore the theft and structural disadvantage that set us back. If we focus only on historical plunder – as Marx helps us understand – we risk paralysis because Marx’s critique explains exploitation well but offers limited guidance on how a country like Uganda should build its future within today’s global system.

The real challenge is to face the truth about our past while still taking responsibility for shaping our future. That requires forging a third path.

READJUSTED COLONIALISM

Colonial exploitation did not disappear; it changed form. Today, it appears as land grabbing in the name of agricultural investment, in corporations claiming ownership over seeds and indigenous knowledge, and huge portions of national income being diverted to foreign debt repayment.

It also shows up in climate injustice, where Uganda suffers damage largely caused by richer countries. The global economy continues to value what we extract from the ground more than what we think, invent, or create.

Trade rules, finance systems, and international institutions often work in ways that benefit powerful countries first. In this context, being told to “just develop like everyone else did” is like being told to run a fair race while carrying a heavy load.

Standard development models pretend history does not matter. They ignore how colonial borders fractured societies, how farming was redesigned around cash crops for export, and how institutions such as the IMF and World Bank often prioritize debt repayment and exports over food sovereignty and industrial growth – echoing colonial extraction in modern form.

THE THIRD WAY

Uganda does not need to choose between blaming the past and blindly copying others. We need a third approach: honest about what was taken from us, and practical about what we can build now.

First, we must openly teach and acknowledge how colonialism distorted our economy. This is not about anger or grievance; it is about understanding the problem correctly so we can design the right solutions.

At the same time, development does not have to follow Rostow’s fixed stages. Uganda must decide its own priorities. Our foundations may not only be roads and schools, but also fair land ownership, reliable regional energy, and control over our digital space.

Kampala city

Our “take-off” sectors should be chosen deliberately – not because outsiders say we are naturally suited to raw exports, but because we decide to build strength in areas such as agro-processing, renewable energy, technology and creative industries.

Second, Uganda must be bold about where development finance comes from. This means stopping wealth from leaking out through corruption, tax evasion and illegal capital flight.

It also means pushing for climate and historical compensation– not as charity, but as what is owed. Foreign partnerships should only be pursued when they help Uganda build skills, technology and long-term productive capacity. Development must reduce dependence, not deepen it.

Third, we must rethink who drives development. Growth cannot be left only to big businessmen. Rostow’s model assumes a Western-style capitalist elite; Uganda needs something broader.

Farmers and miners must be treated as entrepreneurs, supported with land security, tools and access to markets. The state needs skilled, honest planners capable of guiding the economy in the national interest.

Cooperatives – such as Saccos and community energy projects – should be central, not sidelined. Our communal resilience (Ubuntu) is not a weakness to be discarded in the name of “modernization,” but a strength to be built upon.

The informal sector should be integrated with social protection, skills training and credit, not crushed. Education should value science and technology, but also Ugandan languages, history and the arts. A people who know their worth are harder to exploit.

ON OUR TERMS

Uganda’s future will not follow a neat textbook story, nor will it be built by endlessly recounting colonial pain. It will be shaped by careful planning, social solidarity and sovereign decision-making.

We must engage with the global economy without losing ourselves. We must modernize without Westernizing. We must accumulate capital without dispossessing our own people – what scholar David Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession.”

Uganda’s future is not a stage we wait to reach. It is something we build – together. And if we succeed, Uganda can show the world that a country, and a continent, once plundered can still rise with dignity, fairness and self- determination.

0 Comments