Katanga case: Lawyers make their final pitches

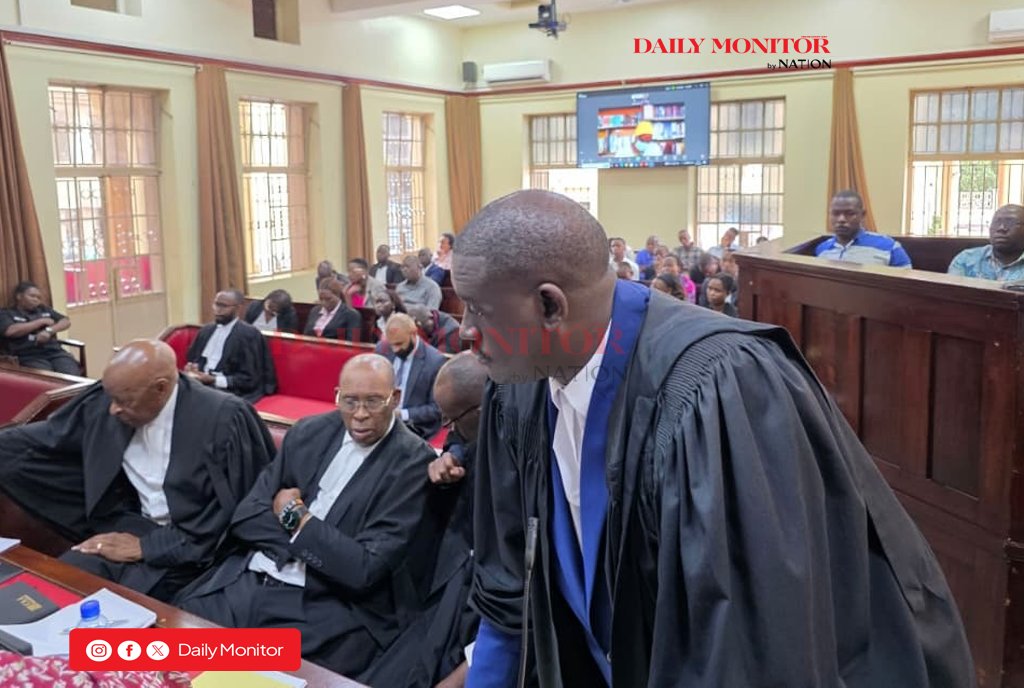

Defence lawyer Elison Karuhanga (right) during the Katanga murder trial in Kampala on October 20, 2025. Photo | Juliet Kigongo

In the Ugandan judicial system, for the prosecution to prove that an individual committed murder, it has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt four ingredients: the human being is dead, the death was caused by an unlawful act, the unlawful act was done by malice aforethought and that the act was committed by the accused.

Yet in their written submissions in which they make a case at the High Court’s criminal division that Molly Katanga shouldn’t be put on her defence in the case in which she is accused of murdering her husband, Henry Katanga, defence lawyers insist that the 25 witnesses that the prosecution led by Samali Wakooli, the Assistant Director of Public Prosecutions, produced were able to only prove one ingredient: Henry died.

In their detailed submissions to Justice Rosette Comfort Kania, Kampala Associated Advocates (KAA), who are Molly’s lead lawyers, assert that their client doesn’t need to say a word in her defence because the prosecution, as far as they are concerned, failed to prove that there was a homicide, that Molly committed it, and that she had prior intent. The case has taken over three years for the prosecution to conclude, amid switching of judges. Defence lawyers insist that the prosecution produced neither direct nor circumstantial evidence that places the pistol that is alleged to have been used to end the life of Henry during November 2024, in the hands of Molly.

To make their case, Molly’s lawyers poke holes into the evidence of Andrew Mubiru, police’s acting director of Forensics, who turned up at court as prosecution witness Number Eight. When he gave evidence in court last year,, defence lawyers compelled Mubiru, who was the author of a DNA analysis document, to admit that his report had no proof that Molly fired the bullet that ended Henry’s life.

Defence’s case

Defence lawyers said Mubiru conceded that a person’s DNA can go onto an object without the person having contact with that object. “During cross-examination, he admitted that if the deceased [Henry] grabbed Accused One (A1) [Molly] by the head, and then he pressed it on the lower end of the door frame and held a gun and pulled the trigger, he would deposit A1’s DNA on the gun. If the deceased touched any surface that the accused had previously touched, he would be able to get her DNA to the gun.

The fact that A1 and the deceased shared a bed for a night means that the DNA could be transferred by him,” the defence lawyers argued, adding that Mubiru admitted that his DNA report could not tell whether the DNA was deposited as result of secondary or primary transfer and consequently he could not answer the critical question of who deposited the DNA. They insisted that Mubiru admitted that his DNA analysis didn’t connect Molly to the firing of the pistol that ended Henry’s life.

The defence lawyers continued to argue that another piece of evidence that the prosecution relied upon was the claim that gunshot residue was found on Molly’s hands in the aftermath of the tragic incident. To prove that Molly’s hands were laced with gunshot residue, prosecution paraded two forensic witnesses: Derrick Nasawali, police’s head of ballistics, and Dr Jaffer Kisitu, a toxicologist. Nasawali informed the court that the gunshot residue could be on anybody in the vicinity of the gunshot.

Nasawali added that the presence of gunshot residue can be seen in proximity to a firearm that had been discharged or came into contact with an object having gunshot residue on its surface. On his part, Kisitu said the presence of gunshot residue is no proof that the person discharged a firearm, and he added that a report can’t be used as evidence that anyone fired a gun. With that, Molly’s lawyers cited the English case of R vs George of 2010 in which the Court of Appeal of the United Kingdom ruled that gunshot residue is evidentially useless.

The UK court ruled that gunshot residue is inconsequential since it may come from shooting, a dummy around or a simple environmental transfer and since no one can say when or how it was deposited, it cannot support any prosecution case. Defence also asserted that the DNA evidence is unreliable to be used in criminal trial. They pointed out that whilst Mubiru in his evidence in chief said Molly had contributed a billion times more DNA that was found on the gun than Henry, during cross-examination he changed the story.

Under cross-examination, Mubiru portioned the DNA portions as follows: Henry 38.687 percent plus or minus 3.277 percent, Molly 43.1 percent plus or minus 2.3 percent and Patricia Kakwanzi 18.2 percent. “The difference between the deceased [Henry] and accused number one [Molly] was four percent and not one billion times,” the defence said, adding that Mubiru’s calculations also revealed that when you apply the margin of error to the maximum percentage you can conclude that Henry contributed 41.963 percent while the minimum for Molly is 40.73 percent. “The claim in his report that A1 contributed one billion times more than the deceased was nothing short of incredible exaggeration from a dishonest witness who was caught red-handed in cross-examination,” the defence lawyers argued.

State’s response

In response to the defence lawyers’ submissions, the prosecution insisted that it did not agree with the defence narrative that it bears the burden to prove to the exclusion of possibilities that Henry’s death was unlawful Homicide. The position of the law, prosecution claims, is that all homicides are presumed unlawful unless it’s presumed to be accidental or authorised by the law. To prove it has proven a murder charge against Molly, the State taunted the evidence of Samuel Musedde, the first police officer on the scene.

Much as Musedde had received a suicide report from Patricia Kakwanzi, one of Katanga’s daughters, who stands accused of trying to cover up for her mother, the prosecution said, looking at the scene and the injuries sustained by Henry, he didn’t believe the suicide story. Musedde’s evidence, the prosecution said, was corroborated by investigators Peter Ogwang and Bibiana Akongo, who ruled out suicide and, as far as the State is concerned, suicide as an invention of the accused, who include Molly, Kakwanzi, Martha Nkwanzi, also a daughter of the Katangas, Charles Otai, a physician, and George Amanyire, the family’s shamba boy.

Making a case that the ingredient of malice aforethought had been proven against Molly, the prosecution points out that the weapon used to end Henry’s life was a gun. The State relied on the evidence of scene-of-crime-officer Emmanuel Alugu, who recovered the gun from the scene of the crime. Olugu said he found the gun in what he termed “ready to fire mode” and that he also recovered a spent cartridge casing and a spent projectile. “It’s the prosecution’s evidence that the deceased died of a gunshot wound to the head. It is our submission that whoever used the gun, which is a dangerous and deadly weapon, intended to unwaveringly cause the death and thus malice aforethought,” the State said.

To prove that it was Molly who actually shot Henry, the prosecution invoked the “doctrine of last seen.” The State told Justice Kania that since there is evidence that Henry was killed from the master bedroom, where he slept with his wife on the morning of November 2, 2023, then it can be concluded that it was Molly who ended his life. “The evidence obtained from accused Number Five, George Amanyire, who was also a worker and also residing within the premises, during the scene construction, is that A1 slept in the same room as the deceased on the night of November 1, 2023. When the incident occurred, both A1 and the deceased were in the same bedroom,” the State said.

The State also invoked Amanyire’s statement, where he said on the night Henry and Molly went to their bedroom, he heard quarrelling and that the door was shut before a blast was heard. Amanyire, according to the State, said the only person who came out of the bedroom was Molly, since Henry was already dead. “The above evidence squarely placed the accused at the scene of crime (bedroom) and this evidence hasn’t been challenged in anyway,” the State said. It added: “The evidence is capable of establishing the guilt of A1 on the ‘doctrine of last scene.’”

To make its case, the State further invoked the case of Uganda Vs Nakanwangi Fauzia of 2015. Therein, the High Court held that since the deceased was last seen alive at the accused’s premises, then the accused had a duty to explain how the deceased had met her death. “With the facts in issue, it would be implausible for one to argue that a person who was last seen in company of the deceased can just walk away without explanation as to what caused the death of the deceased,” the State said.

Retorts

The defence insisted that the State was misleading the court because Amanyire said in his statement that he “heard the woman crying and hearing like someone who is being beaten.” The defence said since Molly emerged from the bedroom battered with blood all-over her, it can’t be construed that she emerged from a scene of violence in command of events. “She is a person who has been overpowered.

Molly Katanga was last seen not as an aggressor, but as a woman subjected to horrendous domestic violence, crying as she was being beaten, silent under assault, bleeding, incapacitated, and in urgent need of medical rescue. That is the evidence of the prosecution for which they intend to rely on the doctrine of last seen,” the defence said. When it comes to the DNA question raised by the defence, the State responded that Molly’s DNA was dominant on the pistol, meaning she fired it. “It’s only A1’s DNA that’s predominant on the magazine and trigger,” the State said.

0 Comments